(If you’re new here and wondering what this is all about - read this first.)

I’ve been told that many parents forget the unpleasant details of their child’s early days - a patina of nostalgia covering up the sleepless nights and sheer terror of an immense responsibility.

I think (for me at least) that the same is true when it comes to the creative process, though instead of merely forgetting the unpleasant details, we tend to forget the mechanism by which inspiration struck and developed over time. Instead, we remember our own nostalgic patina of co-occurring events, emotional states, and how we used our craft (ie learned skills) to translate the creative impulse into something that can be received by others.

It is for this reason that I hate questions about “creative process.” The interesting part is impossible to describe, the co-occurring emotions are often read into (incorrectly), and the craft is often only interesting to other musicians. Artists who write songs with lyrics can often draw from the finished product itself to answer this question (lucky bastards) - but for us instrumental composers, we usually end up stammering through something that sounds highly self indulgent.

Perhaps if we fully understood it, we wouldn’t find the finished product as captivating as we do. But who the hell knows?

Given that I promised a project journal, however, I feel that it’s incumbent on me to at least TRY starting at the beginning. Therefore I’m going to break this first entry on “How to Rebuild” into two component parts:

The craft (or, how I wound up with something on paper that I could contemplate arranging for the studio)

The ways in which my career in the music industry informed/impacted the process

If you’re a musician (or simply bored) feel free to geek out on #1. If you’re a music industry pro with no aspirations to make music, you can skip to #2. If you’re both (which - no shade intended - is my target audience), go ahead and read both. Or don’t, you’re probably very busy anyway…

Craft

As I’ve already stated, I don’t know what exactly inspired me to start write this piece. I do know that I began writing it during a period of lackluster mental health (and by extension, likely a keen sense of my own deficiencies as a pianist). Therefore, a slow meandering refrain was what came to me first.

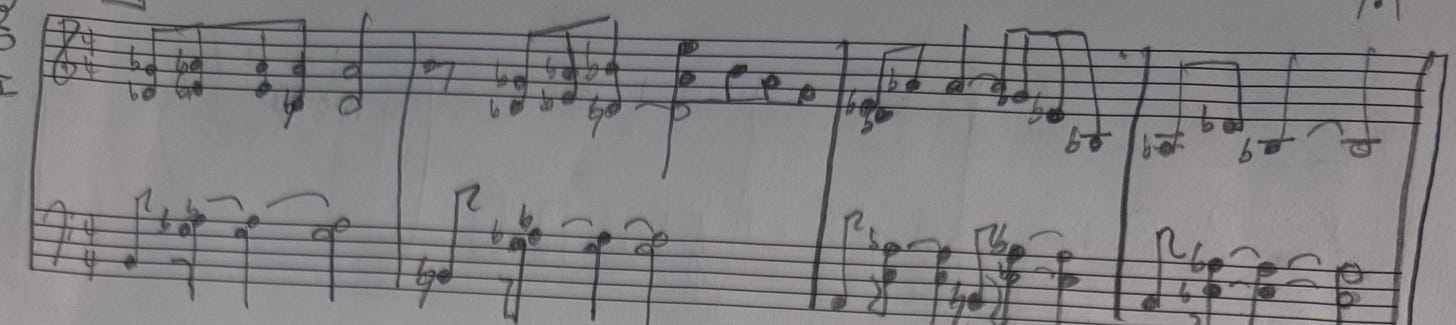

The initial bar of How to Rebuild (my first scribble shown above), was likely something that I simply plodded out during a period of noodling and went - “hey, I like that.” Once I wrote it down, my eye was caught by the simultaneous upward motion of the top and bottom lines and the downward motion of the middle harmony part. Something about the tension reminded me of that melodramatic closeup in a silent film (you know the one I’m talking about - where you see a gauzy closeup of a woman’s face going from hopeful to despairing as she looks away from the camera).

The further I developed that theme without a given form in mind (AABA, Sonata, etc), it became clear that I was in for the long slog that is ‘through-composition’. I believe that this is the point that craft really started to come into play. At this point, it became less of “I have a random idea,” and more of “how do I turn this random idea into something?”

As I’ve already stated, I believe that this where one can begin to answer real questions about one’s work - any point before this and you’re asking the equivalent of “what happened before the big bang?”

For me, the answer to this question was essentially the same process by which an author writes a novel (or a grade schooler writes an essay). I viewed my initial fragments as source material - or themes from which I could draw on and develop into some sort of a coherent beginning middle and end. I achieved this fairly quickly, and realized that 1) it was way too short, and 2) I neglected to explore some of the most interesting themes I initially came up with.

I asked myself - what can I do to make it more interesting? Can I change the key? Yes. Can I change the rhythm? Yes - especially since the first part was fairly rubato.

In this manner I wrote some truly awful “Part Twos” until I finally realized that I had neither the patience nor desire to create a formal theme and variation. But hell, I liked the rhythms and keys, so why not get rid of the rules and see where else things might lead?

As this isn’t a compositional analysis, I won’t bore you with a play by play of the rest of my composition process - but I will say that it became clear somewhere during Chapter II that this was not a piece for solo piano. Which, to be honest, bummed me out, because solo piano is much easier and cheaper for me to record.

…But also created more opportunity - as I was no longer limited in my composition by what I thought would be feasible for me to play on my own.

By the end of my initial paper sketch (shout out Carta staff paper and Number 2 Pencils) I was left with a 10 minute lead sketch of something that, as far as I could tell, had no clear path to ever being recorded or released. I (luckily) hadn’t even begun to consider the work that would go into arranging it. But I had fun, and what I wrote wasn’t lousy, so there was still a feeling of accomplishment.

That is, when I wasn’t confronting “my music industry brain”…

My Music Industry Brain

The music industry is my livelihood. It’s what pays my monthly bills, feeds my baby, and keeps me feeling largely fulfilled during my working week. As such, my brain has rewired itself over the past decade to operate skillfully within this framework - which is highly convenient. I love my “music industry brain,” I truly do.

It can also be a major buzzkill.

As previously discussed, the initial impetus for creativity needs to be somewhat elusive. Our carefully honed craft is what allows us to follow up on those impetuses and put “pen to paper” so to speak (or hand to instrument, or voice to microphone). Already, this combination is a blending of worlds - a methodical and practical reaction to impulses that none of us fully understand. When you add in the “music industry brain,” it shifts the balance somewhat further askew.

Every artist (except perhaps young children) encounters to a tiny bit of “music industry brain” when they are making music. How can one not, after being fed a healthy diet of radio, tv, recorded music, social media etc their whole lives. For most artists this manifests in the core insecurity of - “will anyone listen to or even care about this music I’m creating?”

For those of us with extensive music industry experience, our brains can be significantly more cruel, and with devastating specificity at that. The following are actual (not hypothetical) thoughts I’ve had while writing music:

The artists I look up to and am emulating with this piece don’t have enough listeners on Spotify to be considered “viable.” I’m nowhere near as good as them, so why would I even share my music publicly?

Unless you’ve already “made it,” no one gives a crap about music written by someone as old as me. (It’s worth noting that I am - hilariously - only 33 years old).

I don’t gig that much (because of the music industry job) and therefore no matter how much I write or record I will never be a “real” musician. Why even bother writing anything?

I’m a square, suburban dad with a yearly salary… I haven’t struggled enough for my music to deserve being heard. (When I’m thinking this, I often forget about my two bouts with aggressive blood cancer)

and then there’s my favorite one…

I know for a statistical fact that the audience for acoustic music is rapidly aging and dying off. I also know that the algorithms behind most streaming platforms prioritize either artists that the listener has previously heard or music targeted at younger listeners. Anyone that hears the music I’ve spent years writing is but a mere statistical anomaly.

To be clear… all of these are BULLSHIT. I may very well have listeners who feel this way about me or my music - but for the large part these represent nothing more than my own insecurities. They are certainly not absolutes, and they are (most importantly) NOT HELPFUL in any way shape or form.

It’s amazing the amount of self doubt one has to fight agains in order to see a creative work through to completion. Every step - from the initial sketch, to the arranging, to the recording, and releasing, is another opportunity to put down the instrument/pencil/laptop etc and walk away without taking a single risk. Every coffee break, another chance to abandon ship with a guarantee of making it to dry land.

The truth is, it’s a minor miracle that any work of art is ever completed by anyone who isn’t a sociopath or a clinical narcissist (insert joke about artists here). Just to get past that self doubt and make anything is a victory - doubly so if you have “industry brain.”

I 100% did NOT have this perspective while writing How to Rebuild - and I don’t expect any of you to have it while making whatever you’re currently making.

Having finally released the thing, though, and living to tell the tale, I figure that it can’t hurt to hear the following at least once:

You are making something that wasn’t there before - and that’s an incredible feat that’s been met with awe for thousands of years by billions of people. The recording industry has been around for a little over a century, and has spent a good bit of that time struggling to avoid it’s own collapse. Keep at it.

Best,

David

P.S. Thanks to all who have been purchasing/streaming/sharing my new EP. Y’all are the best. Next entry of “Both Sides Now” will be a bit lighter - I promise.